Joseph Pilates and the Physical Culture Movement

Posted on October 31, 2018 by Movement Health in Physical Culture, Pilates

Pilates gave us his wonderful method of physical and mental conditioning, however some of his ideas were informed by the times and the Physical Culture Movement represents those times. The Physical Culture Movement followed a timeline that started in Europe, moved on to England and expanded in to the United States; Pilates life followed a similar timeline. When we examine Pilates movements and his writing it becomes apparent that he was exposed to thinking derived from Physical Culture.

What is the physical culture movement?

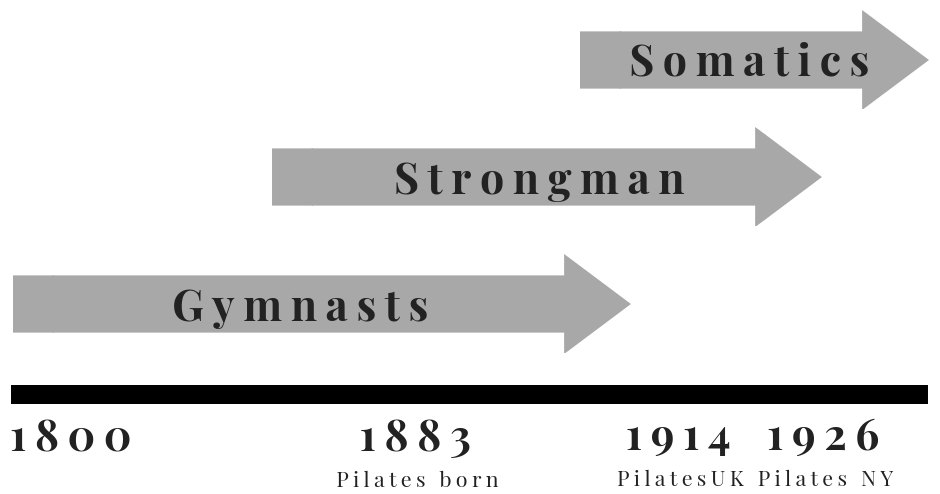

The Physical Culture Movement (learn more here) was a health and fitness movement that began in Europe during the early 1800’s and having spread to England and the United states it reached its peak around the late 1800’s/early 1900’s (McKenzie, 2013). There were essentially three ‘waves’ to the Physical Culture Movement, the European Gymnasts, the Strongman athletes and the Somatics.

The first wave of the Physical Culture Movement began with the European Gymnasts around the early 1800’s. At this time various European nations evolved Physical Cultures rooted deeply in a sense of national history and identity (Pfister, 2003), (Podpečnik, 2014). They emphasised a callisthenic/bodyweight style of exercise and took a scientific interest in exercise and health (Moffat, 2012).

The second wave of the Physical Culture Movement began in the mid-1800’s and involved the Strongman athletes (Watson et al. 2005). They blended the systematic approach of the European Gymnasts with traditional Viking and Highland events. The Strongman athletes are credited with inventing the barbell and were touring entertainers who performed shows that included acts-of-strength and posing in ways that displayed their muscular physiques. The Strongman athletes were more interested in the muscular/physical aspects of Physical Culture and had a more commercial approach (Todd, 1995).

The Somatics Physical Culturists emerged as the third wave of Physical Culture around the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. They had their foundation in the performing arts world and emphasised a mind-body approach to exercise. They emerged for two reasons; the European Gymnasts work was evolving in a scientific direction and what remained was taking on an increased para-military tone due to the looming prospect of war, thus there was space for further exploration of callisthenic exercise (via a Somatic paradigm). Also, the Strongman athletes and their physical/aesthetic ideals were dominating the Physical Culture space at the time and the Somatic approaches were evolved as a mind-body counterpoint (Hoffman & Gabel, 2015).

The Physical Culture Movement was a real presence in popular culture, for most of the 1800’s the European Gymnasts were vying with Competitive Sport for popular acceptance as the prevailing exercise paradigm. Competitive Sport was to claim this mantel when the first modern Olympic games were held in 1896 (Pfister, 2003).

At the Physical Culture Movements peak during the late 1800’s/early 1900’s it was a presence in the popular media, with a ‘Physical Culture’ magazine published in Europe (Drane, 2015) and the United States (Daugherty, 2015).

As we follow the Pilates story we see evidence that he was likely exposed to thinking from all three ‘waves’ of the Physical Culture Movement.

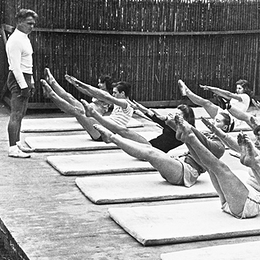

European Gymnast Physical Culturists (Pilates is in Germany)

The German Turner movement began in the early 1800’s and was a presence in European Gymnast Physical Culture. Turnverein clubs played an important social/cultural/political role in liberal ‘freethinking’ German society (Pfister, 2009). Turnen Gymnastics and its politics were inherently intertwined and its goal was to create able-bodied citizens to help build the emerging German nation (Pfister, 2003).

We know that Pilates was likely exposed to a Turner environment during his formative years. Records from 1892 indicate his Father was equipment manager for the ‘Turnverein Eintracht’ (Harmony/Concord club) in Mönchengladbach. Pilates was nine at this time, however his family had been living on the same street as the club as early as 1886 (Pont & Romero, 2013).

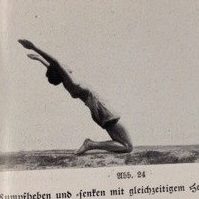

Turnen version of the Thigh Stretch (picture credit)

Strongman Physical Culturists (Pilates is in England, 1914)

Eugen Sandow (1867-1925) was Europe’s most famous Strongman Physical Culturist; he was born in East Prussia (Germany) and founded the sport of bodybuilding. Beginning in the late 1800’s he toured a Strongman act around Europe, this involved posing in a fig leaf as a living recreation of Greek sculptures (Drane, 2015).

A big part of the Pilates folklore is his experience working in the circus performing as a living Greek statue. There is little evidence to corroborate the story; however it’s possible this happened when he arrived in England in 1914. The similarity between Pilates and Sandow’s experience is uncanny. Also a lifelong friend of Pilates, August Benkert whom he met when they were interned in England during the outbreak of World War One indicates in the Pilates Biography that their friendship began because of shared admiration for Sandow (Pont & Romero, 2013).

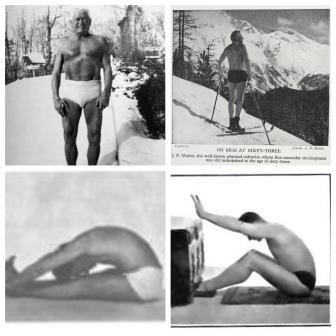

Another interesting Physical Culturist was Jørgen Peter Müller, of Danish origins his philosophy sits somewhere between the Strongman Physical Culturists and the Somatic Physical Culturists. In 1904 he released a book titled ‘My System’ promising improved health via a system of 18 exercises and spending time outdoors (Müller, 1904). This book was an international hit and there are certainly some similarities with Pilates exercises and how the two men presented themselves.

Pilates on the left and Müller on the right

Pilates on the left and Müller on the right

Somatic Physical Culturists (Pilates is in New York, 1926 onwards)

François Delsarte was a French performer who developed a Somatic Physical Culture system that connected the emotional inner experience of the actor with a systematised set of gestures, Rudolf von Laban and Matthias Alexander are said to have studied the Delsarte method. In 1885 a book titled ‘The Delsarte System of Expression’ was published and it’s said Pilates kept a copy of this book at his New York studio (Pont & Romero, 2013).

Dr Bess Mensendieck was a Dutch American medical doctor, who found Delsarte’s methods to metaphysical and evolved the ideas in a more gymnastic/callisthenic direction. She published multiple books on her system and between 1905 and 1924 schools for the Mensendieck System of Functional Exercise were established in Europe and the United States. At its peak there were 200 000 students at her schools and in the 1930’s she was teaching at the modern dance faculties in the New York and Boston Universities (Veder, 2011). We also know Pilates kept Mensendieck’s address at his New York studio and interestingly the address is noted as being next door to his own address (Pont & Romero, 2013).

Following these stories we a see a real picture emerging of Europeans taking their various Physical Culture systems around the world. Some of Pilates connections with these people and organisations are educated speculation and some of them are very real. There is no suggestion Pilates copied these people, however he was likely a product of the times and this is a snapshot of those times.

What was Physical Culture about?

When we examine a lot of the ideas espoused by Physical Culturists there’s some common themes.

Culture

This was an especially relevant theme for the European Gymnasts; Swedish Gymnastics and German Turnen were engaged with their nation’s heritage after having battled (and lost) to Napoleons forces (Pfister, 2003). Pehr Henrik Ling founder of Swedish Gymnastics was a poet, theologian and a student of European languages (Ottosson, 2010). Friedrich Ludwig Jahn founder of the Turner movement was an educator and revolutionary (Pfister, 2003). Both Ling and Jahn were in their own ways trying to change the culture and Pilates is very clear about his desire to change the culture when he introduces the first chapter of his book titled ‘Return to Life’ with the heading “CIVILIZATION IMPAIRS PHYSICAL FITNESS” (p.6), following this he talks about the pitfalls of the modern world and how Contrology can restore physical fitness (Pilates & Miller, 1945).

Another interesting element of culture is the way Mensendieck found herself studying medicine, it’s said she became interested in anatomy via her initial training as a sculptor and was intrigued to the point she decided to undertake medical studies (Veder, 2011).

I find it endlessly fascinating that creators of Physical Culture systems had other lives where they were poets, revolutionaries and sculptors!

Hygiene

This was a big part of the Physical Culture Movement, in the 1870’s as a response to the presence of tuberculosis hygiene was taught in German schools (Pont & Romero, 2013). These classes covered topics such as the importance of breathing fresh air, good sleep habits, nutrition and bathing. The Swedish Gymnastics text titled ‘An Exposition of the Swedish Movement-Cure’ (Taylor, 1860) has a chapter titled ‘Temperature – Physiological Effect of Cold and Heat’ (p.368) and gives descriptions of various forms of bathing and their health benefits. The same chapter also gives instructions for a process called the ‘Air Bath’, this involved rubbing or brushing the body’s surface to bend, stretch and refresh the skin. Müller was also an advocate for vigorous towel-rubbing following a bath (Müller, 1904).

Pilates was a strong advocate for hygiene, he tells us in his other book titled ‘Your Health’ (Pilates, 1934),

“Much of the child’s welfare depends upon the cleanliness of the skin. Water should be freely used. Hot shower baths followed by gradually cooler and cooler temperature until the water is cold, has a most beneficial and exhilarating effect, especially when the body is briskly “massaged” (at the beginning) with a soft brush to be later discarded for a harder one.” (p.45-46).

He also covers this topic in ‘Return to Life’ (Pilates & Miller, 1945),

“The use of a good stiff brush as described stimulates circulation, thoroughly cleans OUT the pores of the skin and removes dead skin too. The pores of your skin must “breathe” – they cannot do so unless they are kept open and freed from clogging.” (p.21).

Spend time in nature/fresh air

With Europeans embracing all things health during the late 1800’s the Freikörperkultur (FKK) movement also emerged in Germany. The FKK was driven by a desire to return to the Ancient Greek aesthetic of wearing limited, loose fitting clothing and the health benefits of exposing as much skin as possible to fresh air (Pont & Romero, 2013). On one level this was a Naturist movement and on another level it was embraced by Physical Culturists such as Sandow who wrote, “Whenever possible, exercise in fresh air” (Sandow, 1897). Müller was also an advocate for the outdoors writing books titled ‘The Fresh-Air Book’ (Müller, 1908) and ‘My Sun-Bathing and Fresh-Air System’ (Müller, 1921).

Pilates makes his feelings on the topic known when he says in, ‘Return to Life’ (Pilates & Miller, 1945),

“By all means never fail to get all the sunshine and fresh air that you can. Remember too, that your body also “breathes” through the pores of your skin as well as through your mouth, nose, and lungs” (p.18).

And ‘Your Health’ (Pilates, 1934),

“The mode of living prevalent amongst the ancient Greeks was, of course entirely different from that of today. These people were nature-lovers. They preferred to commune with the very elements of nature itself – the woods, the streams, the rivers, the winds and the sea. All these were natural music, poems and dramas to these Greeks who were so fond of outdoor life.” (p.38).

Mind Body

Mind Body was usually spoken of in Physical Culture circles when describing the best way to execute the exercises. When describing good workout habits Sandow says in the introduction to his book titled, ‘Strength and How To Obtain It’ (Sandow, 1897), “It is the brain which develops the muscles” (p.13). Mensendieck is said to have developed her own Mind Body philosophy after having witnessed as a part of her medical studies an electrical current being used to stimulate muscle activity and concluded that if an electrical current can stimulate a muscle then so can the mind (Veder, 2011). Again we see Pilates sharing similar beliefs when he says whilst introducing the ‘Guiding Principles of Contrology’ in ‘Return to Life’ (Pilates & Miller, 1945),

“… always keep your mind wholly concentrated on the purpose of the exercises as you perform them. This is vitally important in order for you to gain the results sought, otherwise there would be no valid reason for your interest in Contrology. “(p.11).

And ‘Your Health’ (Pilates, 1934),

“What is balance of body and mind?

It is the conscious control of all muscular movements of the body.” (p.19)

Another aspect of Mind Body that was often discussed by Physical Culturists involved the Ancient Greek civilisation. There was a lot of interest around this topic as a by-product of the first modern Olympic Games being held in 1896 (Pont & Romero, 2013). Sandow would often talk about the ‘Grecian Ideal’ and Mensendieck would reference Greek sculpture, their feeling that the Ancient Greeks represented the perfect civilisation because of their Mind Body ideals (Drane, 2015; Veder, 2011). Pilates felt the same when he states in ‘Your Health’ (Pilates, 1934),

“Were we to discontinue much of our present mode of living and discard our present systems of physical training, and instead, adopt such training as I here advocate, based upon the science of “Contrology” there would result a rejuvenation of mind and body and living itself would again become an art as it was in the days of the ancient Grecians.” (p.39).

Exercise/Movement

I will save a summary of the similarities and differences between the Physical Culturists beliefs around Exercise for another blog post. Most Physical Culture systems spoke of a ‘natural’ approach to movement focusing on callisthenic/body weight exercise and compound lifts utilising only limited apparatus and barbells/dumbbells/clubs.

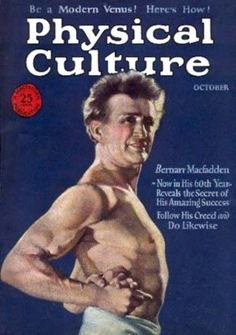

A good summary of Physical Culture is provided by American Strongman Physical Culturist Bernarr Macfadden (publisher of the American ‘Physical Culture’ magazine) who published a Physical Culture creed:

First: Pure air and sunlight whenever obtainable; through ventilation of living rooms.

Second: Wholesome diet of ‘Vital foods, well masticated, eaten only at the dictates of a normal appetite’ frequent fasting of a day or two if need.

Third: Reasonably regular use of the muscular system throughout the entire body in work, in the gymnasium, on the athletic field or otherwise.

Fourth: Thorough cleanliness, which requires frequent baths – cold baths for a tonic, hot baths for cleanliness – thorough dry friction with the open hands, brush or towel is also valuable.

Fifth: Right mental attitude; thinking is a powerful factor in maintaining vital health and can be constructive or destructive. The mind can build you up or tear you down.

After examining the Physical Culture Movement, for me two things become very clear:

- Physical Culturists were the ultimate teachers of self-care.

- Pilates was a Physical Culturist.

Which then leads me to ask the questions?

Do you practice Pilates exercises or the Physical Culture of Pilates/Contrology?

If we’re only teaching exercises and repertoire are we really teaching Pilates?

Thanks for reading, Warwick..

Daugherty, G. (2015). Meet the Wackiest Millionaire Ever to run for President. Money. Retrieved 21st December, 2017 from: http://time.com/money/4074103/wackiest-millionaire-ever-run-president/

Drane, R. (2015). EUGEN SANDOW’S BODY WAS ALL HIS OWN WORK. Inside Sport. Retrieved 21st December, 2017 from: https://www.insidesport.com.au/more-sport/news/eugen-sandows-body-was-all-his-own-work–422597

Hoffman, J. & Gabel, C.P. (2015). The origins of Western mind-body exercise methods. Physical Therapy Reviews 20(5-6), 315-324.

McKenzie, S. (2013). Getting Physical: The Rise of Fitness Culture in America. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Moffat, M. (2012). A History of Physical Therapist Education Around the World. Journal of Physical Therapy Education 26(1), 13-23.

Müller, J.P. (1904). My System : 15 Minutes’ Work a Day for Health’s Sake (Classic Reprint). London, UK: Forgotten Books.

Müller, J.P. (1921). My Sun-Bathing and Fresh-Air System. Alcester, UK: Read Books.

Müller, J.P. (1908). The Fresh-Air Book (Classic Reprint). London, UK: Forgotten Books.

Ottosson, A. & Hansson, N. (2015). Nobel Prize for Physical Therapy? Rise, Fall, and Revival of Medico-Mechanical Institutes. Physical Therapy 95(8), 1184-1194.

Pfister, G. (2003). Cultural Confrontations, German Turnen, Swedish Gymnastics and English Sport- European Diversity in Physical Activities from a Historical Perspective. Culture, Sport, Society 6(1), 61-91.

Pfister, G. (2009). Epilogue: Gymnastics from Europe to America. The International Journal of the History of Sport 26(13), 2052-2058.

Pilates, J.H. (1934). Your Health. Ashland, OR: Presentation Dynamics.

Pilates, J.H. & Miller, W.J. (1945). Pilates’ Return to Life Through Contrology – A Pilates’ Primer: The Millennium Edition. Ashland, OR: Presentation Dynamics.

Podpečnik, J. (2014). ALL YOU NEED IS A RED SHIRT AND CAP; AND YOU ARE SOKOL! Science of Gymnastics Journal 6(3), 61 – 85.

Pont, J.P. & Romero, E.A. (2013). Hubertus Joseph Pilates The Biography. Spain: HakaBooks.

Sandow, E (1897). Strength and how to Obtain it. Kent, UK: Gale & Polden

Taylor, G.H. (1860). An Exposition of the Swedish Movement-Cure. Broadway, NY: Fowler and Wells Publishers.

Todd, J. (1995). From Milo to Milo: A History of Barbells, Dumbells, and Indian Clubs. Iron Game History 3(6), 4-16.

Watson, N.J., Weir, S. & Friend, S. (2005). The Development of Muscular Christianity in Victorian Britain and Beyond. Journal of Religion & Society 7, 1-21.

Veder, R. (2011). Seeing your way to health: the visual pedagogy of Bess Mensendieck’s physical culture system. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 28(8-9), 1336-1352.