The ‘Culture’ in the Physical Culture Movement

Posted on March 14, 2018 by Movement Health in Physical Culture

One of the most interesting parts of the Physical Culture Movement (learn more about the Movement here) is use of the term ‘Culture’. Using the term seems to expand the movement beyond just moving/strengthening bodies and in to subject areas such as society, customs and the creative arts. The largest cultural influence on the beginnings of the Physical Culture Movement in Europe was the Romanticism period (Pfister, 2003). At its peak from approximately 1800 to 1850 and as a counter to the Industrial Revolution the Romantics were interested in European folklore and the beauty of nature (Cunningham & Jardine, 1990).

Prussian/German educator GutsMuths who is credited with the beginnings of the Physical Culture movement via his book “Gymnastik für die Jugend” (Gymnastics for Youth) shares Romantic educator Rousseau’s view that intellect can only be developed through the senses (Rousseau & Wu, 1979) when he says in his book:

“So let us exercise our bodies! Without them we would not think; they are the machines on which we weave the threads of our thoughts.” (GutsMuths, 1793 p.252).

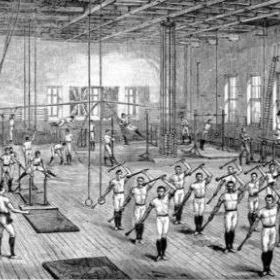

The Turnen Gymnastic Physical Culture organisation was founded by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778-1852) with clear political objectives, they wanted to liberate Prussia/Germany from their French occupiers and dismantle its feudal kingdoms creating a unified German nation. In the Romantic style of the time such patriotism was fostered by referencing traditional German games and songs. The Turnen not only evolved Gymnastics systems but were also a presence in progressive German politics and society (Pfister, 2003, 2009).

Poet, theologian and student of European languages Pehr Henrik Ling (1776-1839) was also exposed to Romantic thinking while creating the Swedish Gymnastics system (Swedish Movement Cure). His written work told stories of Viking folklore and from these he reached the conclusion that the Swedish population had gone backwards physically and morally (Ottosson, 2010). To address these shortcomings Ling founded The Royal Central Institute of Gymnastics (RCIG) in Stockholm. The RCIG was a training institute for Gymnastics educators and emphasised a scientific approach to exercise, this was done by applying the Romantic thinking of the time to better understanding the ‘philosophy of nature’ and studying the ‘laws of the human body’ (Pfister, 2003).

The European Physical Culture Movement was more than Gymnastics, health and exercise; using Romantic thinking as a foundation it came to include elements of ‘Culture’ such as education, politics, poetry and health science. Unlike modern competitive sport, Physical Culture was not just a physical act but one that taught virtues, developed citizens and improved education (Pfister, 2003).

On some level it would appear ideas from the Physical Culture Movement are coming back in to vogue. A whole-body approach to education called ‘Embodied Learning’ has recently emerged (Thorburn & Stolz, 2017) and I see places like Yoga studios not only running Movement-based classes, but also facilitating workshops with themes around personal development and improving the community. Even the emergence in Australia of the health profession, Accredited Exercise Physiologist has seen a strengthening of the alignment between health science and physical activity.

Thanks for reading, Warwick..

Cunningham, A. & Jardine, N. (1990). Romanticism and the Sciences 1st Edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

GutsMuths, J.C.F. (1793). Gymnastik für die Jugend. Gotha, Germany: Schnepfenthal.

Ottosson, A. (2010). The First Historical Movements of Kinesiology: Scientification in the Borderline between Physical Culture and Medicine around 1850. The International Journal of the History of Sport 27(11), 1892-1919.

Pfister, G. (2003). Cultural Confrontations, German Turnen, Swedish Gymnastics and English Sport- European Diversity in Physical Activities from a Historical Perspective. Culture, Sport, Society 6(1), 61-91.

Pfister, G. (2009). Epilogue: Gymnastics from Europe to America. The International Journal of the History of Sport 26(13), 2052-2058.

Rousseau, J-J. & Wu, M. (1979). Emile: or On Education, Introduction, Translation, and Notes by Allan Bloom. New York, NY: Ingram Publisher Services US.

Thorburn, M. & Stolz, S. (2017). Embodied learning and school-based physical culture: implications for professionalism and practice in physical education. Sport, Education and Society 22(6), 721-731.